Show me the money – SVOD or AVOD for monetising OTT?

Digital TV Europe’s recent survey found Subscription video-on-demand (SVOD) came out as the top choice of business model for OTT services. No surprise there, given that SVOD is indeed a great monetization model and often the go to-monetization model for any new OTT venture as it ensures a steady recurring revenue and lock-in effect on users. And you can’t complain about market forecasts either, as by 2022 the European SVOD market is expected to nearly double, and more than 450 million global SVOD subscriptions are expected.

In addition, SVOD makes it possible to receive parts of your monthly revenue with no relating costs. Data collected from our partner SVOD services show that only 60 to 70% of paying subscribers are active monthly users, meaning that four out of ten paying subscribers never accessed or used the OTT service in a given month. This means users are paying a subscription fee without actually using the service, a scenario all too familiar to anyone with a rolling gym subscription. Although short-term this could be considered free revenue, the long-term risk is that those non-active users will eventually churn and opt-out of the service altogether. The premise of getting revenue with no associated support or streaming costs might sound alluring but to achieve real long-term success, the objective should always be to strive for engaged rather than inactive subscribers.

Make sure no money is left on the table

In the same OTT survey, advertising-supported video-on-demand (AVOD) was considered a less promising business model for OTT services in terms of its potential to deliver value to the service provider. Understandable, as sustaining revenue through advertising only can be complex and challenging, but it doesn’t need to be. Today, AVOD should be considered a complementary strategy to an SVOD or Transaction-supported video-on-demand (TVOD) business model.

Incorporating an AVOD-model ensures you leave no money on the table. Monetizing through ads means you can offer limited free content to users that are hesitant to pay a subscription or transaction fee upfront. The strategy then would be to push to convert these free users to paying subscribers through upsell activities, increasing your average revenue per user (ARPU) and the customer lifetime value. In an ever more competitive market, using an ad-supported freemium model will also help with marketing efforts as you’ll be able to attract and onboard new users who want to try the service for free first. You can still monetize through ads as you convert them to paying users.

Even though AVOD doesn’t offer the same steady revenue stream or the same level of ARPU as SVOD, you shouldn’t overlook the revenue opportunities from video ads. Case in point, according to research by MonetizePros.com, YouTube’s cost per thousand impressions (CPM) range from $18 to $24 depending on the type of ad shown and Hulu’s average CPM can be as high as $28. Looking at connected Smart TVs, a rough average is around $25 per video ad CPM. You can’t ignore these CPM levels and sources of revenue.

The increasing interest from marketers for OTT as an ad channel is also easy to understand. Viewers are spending more and more of their time watching OTT video compared to traditional TV media. According to eMarketer, 7 in 10 Americans are now consuming ad-supported OTT videos regularly, and this is expected to grow considerably in the coming years.

Another advantage of using OTT as a platform for video advertising is that it enables you to capture rich viewer data, resulting in much better targeting of relevant video ads. CBS All Access, in fact, reduced their video ad inventory (and cost) for OTT content by 25% as they were able to target audiences much more efficiently based on the detailed viewing data collected.

AVOD, coming to an OTT screen near you

We’re still only in the early phase of the shift and uptake of video ad spending for OTT video. Research by MTM and SpotX showed that at the end of 2017, 30% of all video advertising was spent on OTT services. And it’s projected that video advertising delivered over the internet to TV screens will be worth more than €825 million by 2020, with compound aggregate growth rates (CAGR) between 20 to 80% in European countries.

At Magine Pro, we believe the secret to a successful OTT business lies in a business model that combines SVOD, TVOD, and AVOD whenever possible. As part of our video solutions, we offer SVOD, TVOD, and AVOD business models, either separately or combined in an OTT service. The Magine Pro platform is also pre-integrated to SpotX ad server, enabling our partners to generate ad revenue by direct deal and programmatic advertising, and extensive ad campaign management. Essentially making it extremely easy for new OTT services to start monetizing through AVOD from launch as efficiently as possible.

You can find out more about Magine Pro’s video solutions and monetization models here. If you would like to speak with us directly via phone or email, please contact us.

The key to building a successful OTT business

Disney’s recent acquisition of BamTech, the OTT video platform arm of MLBam, should come as no surprise, and likewise, Disney’s announced the creation of a stand-alone streaming service and removal of their content from Netflix. It is only another example of more networks and content owners embracing the direct-to-consumer strategy, bypassing traditional distributors, and bringing the number of OTT streaming services and competition to an all-time high.

With deals like Disney’s, the blurring of boundaries between content owners and distributors is ever increasing, as is investments in programming and original content by traditional distributor-only’s and tech players, with Netflix taking the lead with their $8bn content investment for this year alone, followed by Amazon’s $4.5bn, HBO’s $2.5bn, Alibaba’s $2.4bn and Apple’s $1bn.

For a new entrant streaming service, wishing to win the consumer’s eyeball time and monthly streaming budget, both of which are finite, the consequence of this highly competitive development is the requirement of potentially vast investments in content and marketing. But by using an end-to-end managed service OTT platform such as Magine’s, new OTT streaming entrants can minimize the CAPEX and OPEX required for the setup and operation of an OTT service, enabling capital to instead be funneled into content and marketing, ensuring they stay ahead of the competition, as well as eliminating the risks associated with technology investments.

It’s undeniable that competition in video streaming services is fiercer than ever but based on Magine’s experience of working with and launching a wide array of services, we’ve put together a white paper on what we consider key to building a successful OTT business.

Within the paper we cover how to attract and keep your audience engaged, reduce churn and expand into new markets, alongside the importance of choosing the right tech solutions, analytics and monetization models for your content and business. Download the white paper today and read more on what we regard as critical to launching an OTT service and how our global solutions can help get you off the ground.

Download the white paper here or contact us directly to talk more about Magine’s solutions business@magine.com.

The adoption of cloud technology to deliver mainstream TV services

Digital TV Europe recently launched their 2017 Multiscreen & OTT series, which looks at four distinct developments: the emergence of new mobile-centric services for millennials and Generation Z; the prospects for cloud-based targeted advertising; the launch of Amazon Channels in Europe and its likely impact on the pay TV business; and the adoption of cloud technology to deliver mainstream TV services.

Rahul Puri, general manager of Magine Digital Media and CTO at Magine shares his views in part 4 of the series, Cloud TV, about the key requirements of getting an OTT TV service up and running. Rahul says “A fully functioning OTT TV service should actively engage customers with high-quality content, strong user experiences and attractive pricing models – i.e. subscription, PPV etc. Services also need to meet the expectations and demands of today’s user and provide high-quality video streams that can be watched anytime, anywhere.” He adds, “Magine’s media platform is built to accommodate all of these requirements in an integrated way, in addition to offering deep analytics that can inform decisions relating to the content acquisition, user engagement and monetisation.” Within the interview, Rahul also talks in more detail about the advantages of outsourcing platform requirements to a third-party online video platform provider like Magine and shares some of the key lessons we have learnt through owning and operating our direct-to-consumer businesses.

Download the series for free today from DTVE’s website to read Rahul’s interview in full. You can also contact us directly if you would like to discuss Magine’s global end-to-end solutions, or, arrange a meeting at IBC this September and meet the team at our stand.

Introducing Sappa Play by Magine

TV doesn’t have to revolve around the living room, and as we consume more content on mobile devices, it’s no surprise that the demand for quality streaming services continues to rise.

Last month we announced our latest project, a complete TV Everywhere solution for Swedish broadband and TV operator, Sappa. Built on our proven platform, the Sappa Play service delivers live TV and catch-up content to over 50,000 existing Sappa customers.

Hasse Svensson, CEO at Sappa says, “In line with new TV viewing behaviour, we as a company must adapt our customer offerings with a good TV offer for mobile screens.” He adds, “We have evaluated several solutions on the market and finally chosen Magine’s overall solution that will give our customers a great user experience. The implementation of the new service has really gone smoothly, and we can now launch a complete streaming service to our customers before the summer. ”

Leveraging our experience in the consumer market and the latest streaming technology (not forgetting our talented team), we’re able to provide Sappa with a secure and scalable solution that’s cost effective, user-friendly and available on all multiscreen devices; supporting the web, iOS and Android.

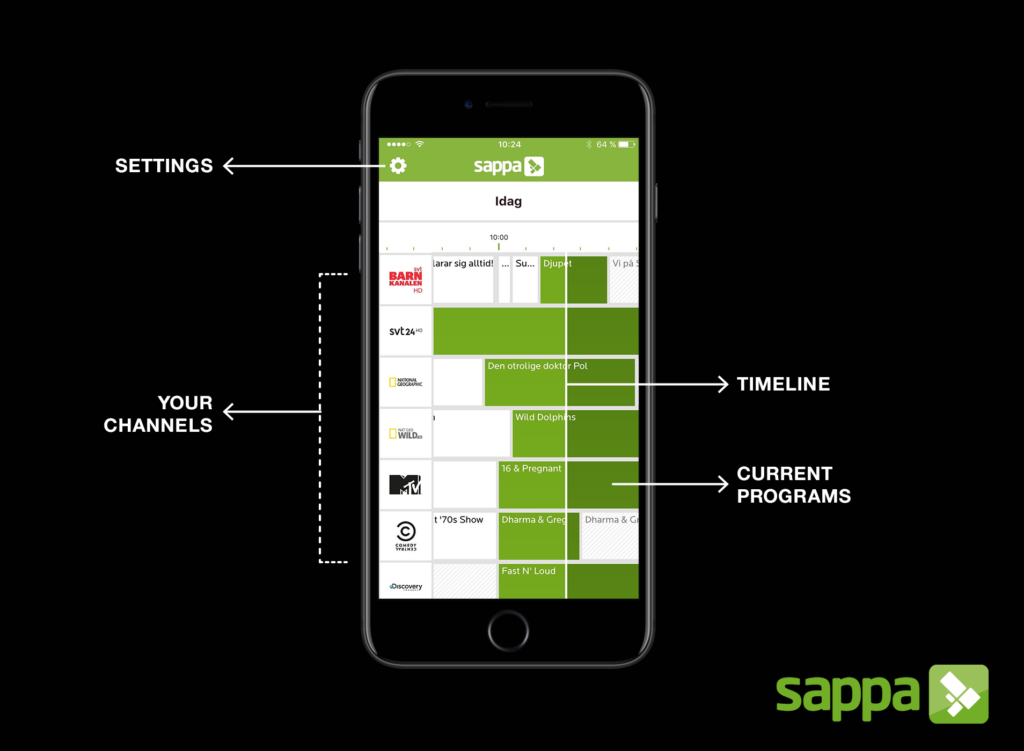

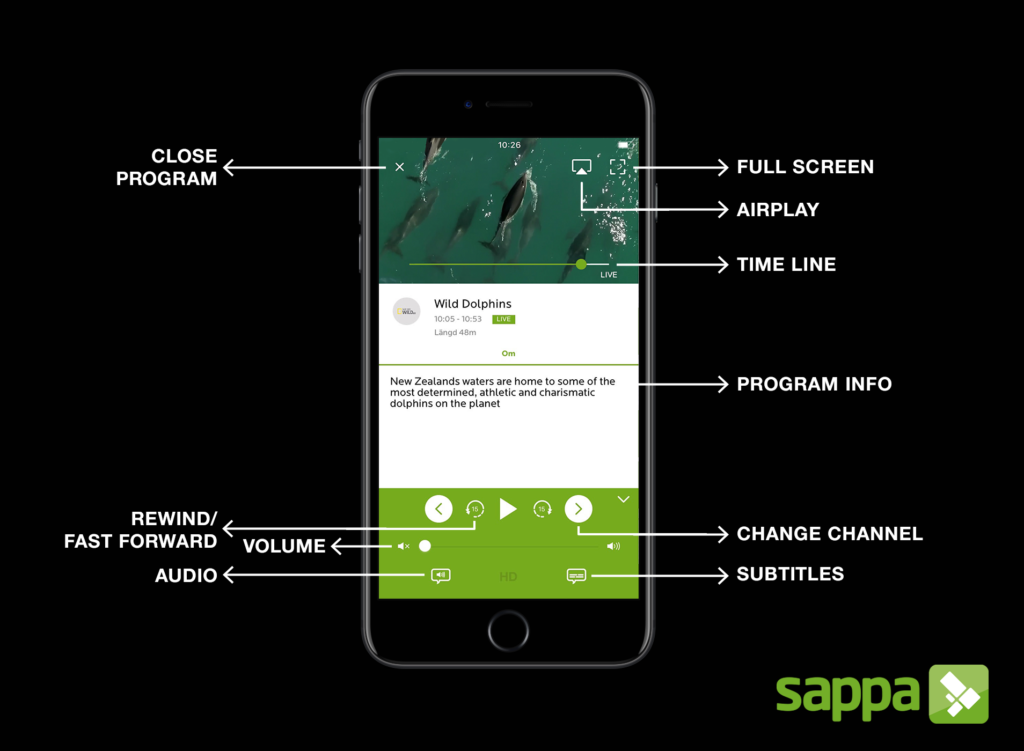

Here’s a sneak peak at the Sappa Play service:

The Sappa branded interface includes features such as rewind on live TV and catch-up functionality, not forgetting a fluid EPG that enables users to scroll through the timeline (past and present) to discover what’s on.

To find out more about the Sappa Play project, check out our case study or get in touch to chat.

Additional Links

Download Sappa Play iOS | Download Sappa Play Android | Watch TV via Sappa Play web

Live Channels v VOD

The channel is dead, long live the channel.

I have a confession to make. When I left Channel 4 ten years ago, to join BT at the start of its journey into television, I thought that with the advent of video on demand (VOD) the channel could eventually be dead. It was already clear at that time that consumer behaviour was changing, as new tech was enabling viewers to watch the content they wanted, when they wanted, on multiple devices in and out of the home.

Today, in the march to digital distribution and with the continued global expansion of OTT services such as Netflix and Hulu, many content owners and broadcasters, including HBO (HBOGo), NBCU (Hayu), Disney (DisneyLife), Sony (Animax), are asking the same question and exploring complementing, and in some cases substituting, their channels with a VOD proposition. In doing so they are raising fundamental questions about their business model. Should they go direct to the consumer (who they haven’t traditionally had a relationship with) and bypass platforms, and should they monetise via pay subscriptions or through advertising?

Ten years on and with the benefit of working at the forefront of OTT TV with Magine, my view on whether the channel is dead is rather different and more nuanced. My conclusion is that channels are still relevant in a digital world of OTT and here are five reasons why I think this is the case:

1. CHANNELS ARE SOCIAL

Viewers like to watch programmes that are socially relevant, whether it’s watching an event with friends at the same time such as live sports or watching a programme they can talk about and share with others later on. The schedule of a channel helps create a mass social experience. While it is attractive to be able to binge watch series via SVOD, if no one else is watching and you cannot talk or share your views on the programme it can feel isolating.

2. WE ARE LAZY AND LIKE BEING TOLD WHAT TO WATCH

Ever been in a restaurant, and while leafing through the menu you wish the head chef would come out and recommend what to eat? Viewers still like being guided by an editor, the art of scheduling and commissioning is not lost. In this scheduled environment we also like being surprised and watching programmes we hadn’t otherwise thought about watching.

3. LIVE IS STILL KEY

Live events such as sport or talent shows work best on channels. They help create, build and share the tension, joy and passion of this programming. Advertisers also value the mass reach and ability to connect to large audiences at the same time.

4. MILLENNIALS STILL LIKE TV

While younger generations consume a wider range of media, TV is still popular. It may not be as dominant a media as it is for older generations but it’s still one of the most important, they just consume it differently, on multiple devices and in multiple locations.

5. TIMESHIFTING MAKES CHANNELS STICKIER

There are a lot of programmes viewers prefer to watch live but they also want the freedom to watch something 30 minutes to two hours later or even the next day. A cloud-based TV service, like Magine TV, enables users to pause, start over, and catch up on programming in and out of the home.

The fundamental challenge for TV is not the channels themselves but discovery. The way in which viewers select channels and programmes hasn’t really changed in the last twenty years, as all the innovation has gone into the delivery and discovery of VOD. When we lived in a world with four or five channels there was limited choice but it made things easy, in a world with hundreds of channels and lots of choices, finding the right programme can be frustrating. In an increasingly image-rich world, most viewers still have to scroll through a list of channels on their EPG to find something they want to watch. At Magine, we are looking at new ways to engage the viewer and help them discover live content, simple options like enabling customers to scroll through pack shots of live programmes as well as VOD, and allowing them to add reminders and create a ‘Lineup’ of live and VOD programmes to watch.

The response of many, although not all broadcasters, has historically been to create apps that separate VOD from the channel experience. In some apps, the channels were not even present or they became an afterthought to the consumer experience. This seems strange when the viewer only really cares about great programming, and they typically prefer all their favourite channels in one place.

Here at Magine, we’re attempting to solve these challenges for our customers and our partners. For broadcasters and customers, a lot is at stake. In the UK, c.£4.3bn in advertising revenues and £6bn in subscription revenues is derived predominantly from linear channels, and broadcasters are investing c.£6.4bn per annum in content. In Germany, a similar picture emerges with c.£5.3bn in ad revenues and £5.85bn in subscription fees from channels. In comparison, while Mintel suggests that the UK streaming video subscription revenues will rocket from £437m to £1.17bn between 2014 and 2019, even with the growth in SVOD revenues, it is clear that the continued success of channels will be key to maintaining the overall level of content investment in the ecosystem.

Broadcasters have invested a lot in content over the years so there is some fantastic programming out there, it’s just a case of improving the user experience and making it easier for the viewer to find what they want to watch. However, as broadcasters rush to create their own VOD apps they effectively create a walled garden around their content, making discovery harder, not easier for the viewer. It also seems unlikely that the consumer will want so many apps on their devices. In a digital world where there’s a larger choice of channels, catch-up, SVOD, there is significant value in aggregating and simplifying the experience so viewers can find content via one app.

At Magine, we believe that OTT can complement and reinforce existing business models rather than tearing them down and that channels can sit alongside VOD in the digital world.

Content Piracy: Where there’s no will, there’s no way

In America during the 1950s, there were regular sessions of a body named the House Un-American Activities Committee. These sessions were like TV series in themselves in that nobody really knew what was going to happen in the next episode.

Content-wise they really shouldn’t have had much to do with film and TV at all, but they did, and in one of these sessions they hauled up screenwriter doyen, Dalton Trumbo, to ask him what his position was on the so-called Hollywood blacklist. It seems he answered, “At the top of it I think”.

Wit under pressure is a testament to the man’s talent, but after they’d jailed him he found it tough to put his talent to work, and as a result, he became one of the first victims of piracy and actually promoted it himself. He worked out that the only way he could earn a living was to secretly write stuff like Roman Holiday and Spartacus, then let other people steal the scripts so he could split the booty when they were picked up by Paramount, MGM and the Academy Awards jury. Only in America? Perhaps, but it was a sad time for artists like Trumbo, as well as for the US.

Maybe not surprisingly for a country blessed with peerless storytellers, its people can turn their commercial hand to any writing at all. For example, the growth area I’ve been struck by most recently, centres around their car-bumper stickers. These now no longer limit themselves to telling you whether you are in the Sunshine, Peach or Wonderful Life State but they now also impart 10-word shards of insight that leave you wondering who is laughing at who. Best of the current bunch is the one on the back of those mirrored-steel trucks and SUVs, which burn up the plains from east to west. It reads: “Well, at least the war on the environment is going well…”

A cracker, you’ll agree.

But it’s no less fun back in television. There are times when the topic of piracy in TV gives rise to the same kind of end-of-days comedy, and this is all the harder to understand when you consider that audiovisual piracy accounts for billions in lost revenues in the TV business, and that’s just in the US. Season six of Game of Thrones has just ended and it’s hard to imagine what the Iron Bank’s iron-faced managers would say if they knew that twice as many people had illegally watched their mythically expensive series for free, as were watching through good old premium pay TV (approx average cost for a package containing the series: €50+). It would probably be something like, “My office at 9 o’clock sharp, Mr HBO. And bring your leaky technology partner with you”.

The problem gets worse not better as HBO and others wriggle to compensate for the losses: either the consumer price of pay-TV packages rises, with the €100 summit long-since scaled; or it fragments into indecipherable programme quantums, which add up to more than that; or it just gives itself another complicated promotional twist and generally gets people’s backs up. Nothing creates a thief faster than an unjust price for bread, and likewise, nothing gets a pirate reaching for the nearest illegal website faster than a programme they feel they’ve got a right to see but can’t.

There are times, we have to admit when our industry looks like it’s really trying to go the way of private medicine and high street banks – that is, convert itself into the product nobody wants to pay for but sometimes has to. If you think back to when Sky kicked off their coverage of live events at the end of the 1980’s there was a definite belief that they had improved the viewer experience and dragged some of our quaint old sports into a new digital era of spanking images and wall-to-wall emotion – think The Masters, The Ashes, The Champions League. And in the process, they seemed to make their 50 quid a month asking price sound like a favour to the armchair viewer. No complaints there – we were happy to pay for that, weren’t we?

Fast forward though to the cash-strapped modern fan recoiling in horror at suddenly having to pay not one, but two subscriptions to follow just one team in one league. What are we financing now, they ask? Some kid’s third or fourth Maserati?

And to add to this general queasiness, TV viewing has changed at quite a pace, with TV viewers now on the move more than ever, and wanting to take their programming with them. Whether it’s in the garden, on the bus, away to their student flat or just on holiday. But whatever the direction they move in, they don’t want to trouble their minds with rights, device restrictions, SD not HD, or messages which tell them, “Not available on this brand new TV set”. Basically, they have no truck with any of the industry pillars which operators like Magine have to help keep in place in order to keep their word to the programme makers.

It seems that right now, viewers have already made that self-justificatory journey which tells them, “I already pay enough for TV shows – I am perfectly within my rights to steal this programme”. Hence we get rampant piracy, led by the most innocent in the class – our kids.

But is there any real will to tackle this? OTT operators like Magine have spent tens of millions on technology to track TV usage and to protect programming. On top of that, we have poured our admittedly entrepreneurial efforts into clearing rights with every artist in the food chain, from the Hollywood studio to the composer of the credits sequence ditty. And yet legal, monetizable viewing via the internet is still forced to jump through a thousand unlikely hoops by the same content creators/producers/distributors. Why is this? OTT may have the tools to tackle piracy and return most of the lost billions, but there just doesn’t seem to be the will to let them do it yet. Or at least to help them do it by pursuing with the same bite, the TV operators who just take signals without asking, or don’t give guarantees on content protection. Try doing that with water, electricity or even a hotel coat-hanger.

Meanwhile, with the passive acquiescence of most of the interested parties (creative, industrial, governmental), millions of viewers either take out satellite subscriptions in countries where they do not live or copy and share programmes daily. Or just find a website that does it all for them. Lets call it a fully-turned blindness of the eye rather than active permission, but it goes on. Because after all, a pound is a pound. Except that right now, it is illegal and left unchecked it pulls apart the broader process which creates and produces the programmes we watch.

It seems the EC may normalise part of the modern viewer’s behaviour by allowing some sort of rights portability between member states. Hats off to them as a public organisation for doing that. But they could be held up by the tricky issue of how to track usage accurately and therefore keep an eye on where – and for how long – viewers are stretching their TV watching rights. Are we on a two week holiday in Ibiza or did we move there in 1992? And if we did, should it matter if we pay our license fee in our country of residence?

The slightly weird thing is that with OTT technology and cloud-based rights management, there is no need for this TV twilight zone to exist, or for pirates to be actively encouraged by abusive or incomprehensible pricing. Magine (and perhaps others) can block illicit viewing down to the accuracy of a postcode. And can allow it where it has been properly paid for, either via license fee or subscription. With a simple flick of the ‘cloud switch’, British viewers would be able to watch the BBC on holiday in Amsterdam and Americans, the NBC in Abu Dhabi, and they would not infringe a single law, upset a single local operator, or deprive a single artist of their due reward. It’s just about precision rights management and the will on the part of the content owners, to back it.

And what are current operators doing to rein in those galloping piracy stats that are making off with their revenues and their partner’s programming? Well, if you were to judge purely on results you’d have to say that whatever it is, it’s not working. The BBC is about to end a two-year ‘consultative process’ to license its channels to OTT operators. Whatever went on in that vast investigative exercise it came up with the idea that restricting mobile devices to in-home viewing would be a good idea. To describe this as swimming upstream would be an insult to salmon everywhere – is there any chance at all of a viewer understanding why their tablet stops showing a programme when they walk outside? Or why they can’t tune in on 3G if the coffee shops wifi is down or a bit slow. Start doubling the piracy stats.

Netflix, on the other hand, originally prided themselves on easy access and a simplified pricing model which they claimed was reducing piracy from 20% to an acceptable 7%. We would share their pride if the story stopped there. In fact, what they were really doing was allowing subscribers to access their content anywhere in the world, via VPNs and proxies, with all the viral effect that had on sales. They then took steps to block this illegal practice, but only when it started to mess with their new licensing business, which lo and behold, was actually making more money for them through selling rights to broadcasters territory by territory – the very system they set out to ‘liberate’ us from with their binge-when-you-want approach.

Why did content owners not push them to plug this leak before, as an OTT distributor like Magine would be forced to do? The easy answer is because some operators really were OTT in what they were paying for those rights. And there is no difficult answer.

In other words, the rights holder’s position was, ”The billions I’m losing to piracy is already written off, and anyway it isn’t quite as important this year as the €100M I can get right now on my shift to make the numbers square up. And if I’m crafty with the PR, the local broadcaster (who’s also bought my series for stacks of cash) will blame piracy, not me….”

So they sup with the devil and give the can a hearty kick down the internet highway. But then, in the end, some poor soul has to pay for this and that will be the viewer who still follows the rules. It will always be those who fork out unthinkingly each month who foot the bill, whether it’s because they don’t miss the money because they believe it’s a fair price, or simply because they have never knowingly broken the law and feel uneasy about doing it.

And anyway, it isn’t all gloom, is it? The Aereo case in the United States showed that it is possible to act against operators who access content without the permission of the owner. Except that, it is just one case which has not been applied yet to any similar cases outside the US.

So the message you can begin to glean from this is; don’t be too sympathetic when you read that by midnight on Monday the 25th April, just 21 hours after the latest Game of Thrones premiered, 10 million illegal downloads of Episode One had been detected just in Australia. Because the truth is, nobody very big is really that worried about it yet, and if you are a pay TV subscriber, you’re the one paying for it anyway.

And so the operators hope that while you are pitying them as you would a friend who’d just been burgled, you won’t notice that your subscription price has just taken a hike upwards. There really are no free lunches in this and the unspoken digital rule is that a worldwide, virally-marketed piracy business can do wonders for the visibility and future sales of a product. High-profile, globally simultaneous releases have just sexed-up the challenge. Cool pirate captains the world over, now want to ‘watch-it-for-free and chill’.

So while enough remaining viewers continue to pay inflated prices for their rigid TV package and while nobody feels like backing legitimate OTT solutions to track their content properly we can all rest easy and look forward to getting a consolation sticker on next month’s pay TV bill. Something like “At least the war on piracy is going well”.

Global TV: A thing of the future?

Johan Cruyff died in March, and for the three of you who don’t know who he was, this guy was a handsome, floppy-haired footballer from Holland, who transformed sport, television and the Dutch in the seventies.

He appealed to radically chic daughters and seventies-meek mums in much the same way Bowie did, or in the same way someone like that would do now; if there were anyone like that. He was one of the first global TV products and yet remained as slim, elegant and local to the proud Dutch as a tulip.

By speaking his mind – whatever came into it – he innovated constantly and challenged ideas just as often. But he was also pretty interested in making money out of his art, believing that the local baker in Barcelona, where he lived happily and died, would not give him free bread when he was 65 just because his name was Johan Cruyff. His universal appeal meant that people across Europe wanted to see him play every week and wanted to hear him give authority a clip round the ears every time he met a journalist. It helped in no small measure that he was a genius, and when he turned football into a global product by playing for the New York Cosmos, at a time when television couldn’t distribute global products, it was just another example of him seeing the future before it came. As he said at the time, “I only seem fast because I start running slightly earlier than everyone else”.

The Premier League didn’t have a Cruyff in the nineties but in one way at least it has been even more successful. They went about building the biggest worldwide show on offer through a tidy combination of velvet-green HD pitches, a clever historic ‘home of football’ brand, and a dose of piping hot stadium atmosphere. Where Cruyff was just playing how he saw it, speaking how he felt, and wearing a dashing orange kit, the EPL were completely rewriting the rules of live television without even mentioning the football. And they took the result everywhere, flooding that same ‘home of football’ with more revenues (and visitors) than the BBC, ITV, Channel 4 and Sky combined. The EPL is now truly global and wondering how it can stop people like pub landlady Karen Murphy from challenging its right to license football rights country by country by using a Greek decoder to show the Premier League in Portsmouth. Or even, if it needs to stop her.

So television has already gone global through what we should call the ‘viewer pull’ of a charismatic rebel and the ‘content push’ of marketing masterminds.

At the same time, there’s another spin to global television afforded by technology, which doesn’t have the same ‘James Bond villain’ ring to it. How about just making it easy to watch the programmes you want to watch wherever you are, for no better reason than the fact that you’ve paid for them? Or, helping a TV producer distribute a quality series that got a 35% viewing share at home but didn’t get any international buyers because it was up against a €25M blockbuster hit like The Night Manager. It could even be because the series was made in German and nobody fancied footing the subtitling bill. Or, because there’s an elusive insurance policy which TV Execs look for in an acquisition and which can be summed up as, “If I buy this and it fails, I won’t get sacked because everyone else has bought it”.

Or, how about giving a content producer the tools to target, track and monetize any programme they distribute, anywhere in the world? Audiences everywhere paying just enough to keep the cameras rolling and the storytellers telling, but not too much to make them turn to, or return to piracy.

These are the challenges that OTT was made for. Help out the viewers as they try and make TV theirs again, make watching a programme almost unethically easy, keep the revenues flowing back to the programme-makers so they can stay creative, and lastly, give some kind of human meaning to pat corporate phrases like global TV. What worldwide television ought to mean, outside its legitimate need to get paid for its programming, is that back in the day, anyone would have been able to follow Johan Cruyff any day of the week and twice on Sundays. But only if they were interested in doing that.

Image Credit: Johan Cruyff in 1987 by Rob Bogaerts (ANEFO). Image Rights.

It’s TV’s time – Finally

It is an incredible time to be a part of Magine. We are finally experiencing the opening up of the information age for live television, which means we are now able to serve the generations that have been formed by it.

The magic of genius storytelling, live performance and high quality crafted production is now consumable uninterrupted, from anywhere, in any flavor, to wherever. And it is happening fast.

Until recently, two fundamental barriers have been in the way. The first being the basic delivery mechanism, which couldn’t support the viewer letting go and getting lost in a riveting drama, or entering a mental stadium for the tense final minutes of their team’s season, without the risk of things breaking down – disaster. Viewing online or on the phone has always been a nervous high-wire walk, resorted to only in emergencies or for lower value nibbles, never glorious TV feasting.

That has all changed. You can now be brought to tears, or to your feet by staring at a phone.

The second barrier has been availability; finding something we want to dive into and watch, no matter where we are. The content we wanted to view, has often been restricted by something mysterious going on backstage – the rights paradigm.

And rightfully so – bloody good thing. Blowing up the control over where, when and by who access to the best entertainment in the world is granted would mean less to view, not more. It would mean punishing, possibly crushing the creative source of what moves us most.

This is the industry’s high-wire act. How do we gently move from localized, controlled provisioning to opening up to discovery of all the world’s greatest TV?

This too is happening. In fact, the biggest moves are being made by those with the least to lose. Those still dependent on the local model now need to embrace experiments for new audiences – there is more to gain if we move together smartly. But we have to move.

Magine at its core is a wild mix of brilliant engineers and designers, of responsible content and rights experts, and of digital business pioneers. We are all working on the same thing; sometimes boldly bounding, sometimes carefully stepping into the deep end of TV’s Time. Right now we’re working on developing what we call the TV Superhighway, the new partnership playing field for viewers, creators and entrepreneurs to all win together in the new arena.

Game on.